Certain: empirically attested: scan of actual find.

Quite certain: must have been present by logical extension of class 1 and low potential variability in colour and shape.

Moderately certain: object must have been logically present, but precise shape and colour uncertain. Based on parallels. Limited potential variability

Not so certain: like previous but parallels give more options. High potential variability.

Quite uncertain: interpretation based on general stylistic traditions

Very uncertain: there is no indication that object was ever present, purely theoretical.

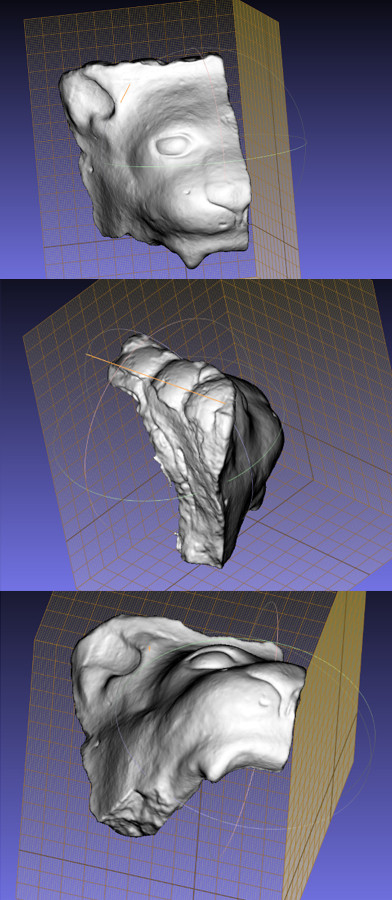

The scanned object

The scanned object is part of a group of almost 300 fragments of architectural terracottas that in the 6th century BC belonged to a temple at the modern site of Caprifico near Cistern di Latina, in central Italy. Only the upper right half of the head was preserved. It is clearly a feline creature, perhaps specifically a lioness. The scan was made with a DAVID structured light 3D scanner.

The start of a reconstruction or digital restoration project starts with study of the object by detailed visual examination of the geometric propreties of the object. What do damages and preserved geometry indicate about the missing parts?

Hover or tap the bullit points to learn more.

The reconstruction

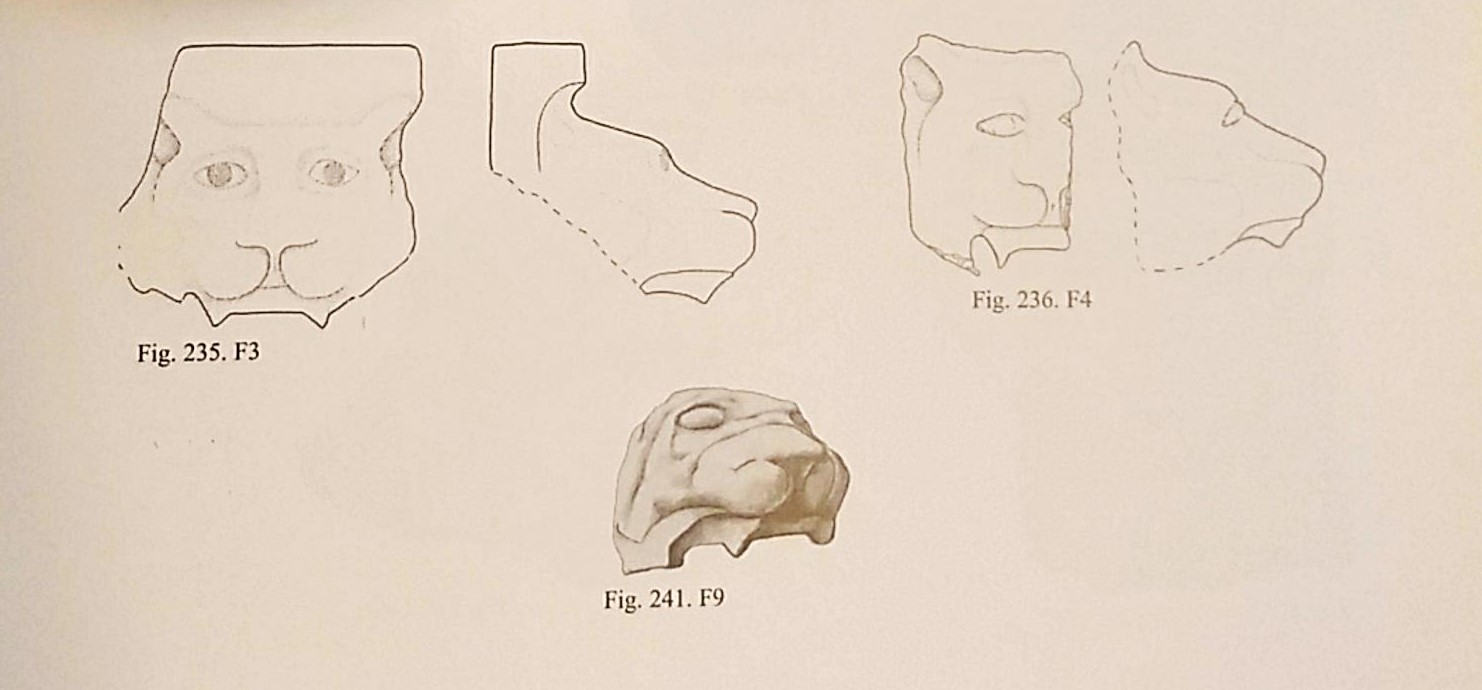

For the 3D reconstruction, or perhaps more accurately, digital restoration, the geometric properties of the object itself are closely examined, and a comparative study was made. Only three lion heads survive amongst the 300 odd fragments from the Caprifico temple. Interestingly, the three are no exact copies of each other. All these heads only had the upper part preserved, so we do not know exactly how the lower part or mandible looked.

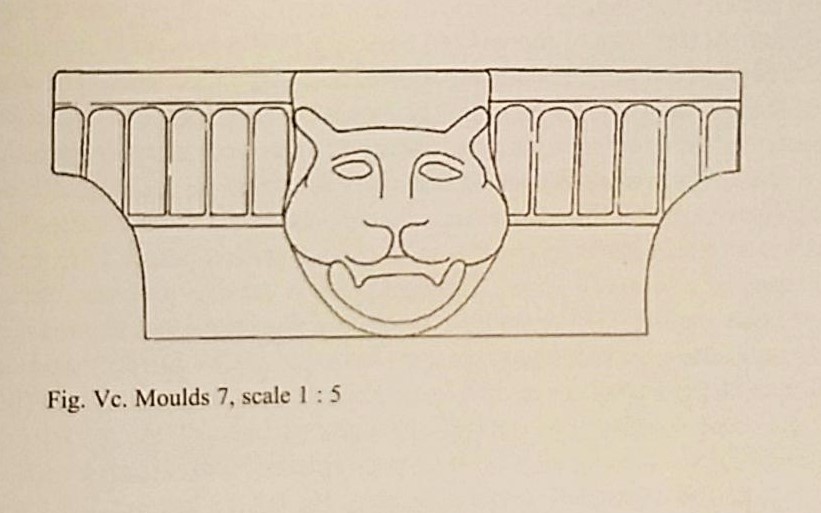

The lion head waterspouts from the temple of Caprifico (after Lulof 2010).

The lion head waterspouts from the temple of Caprifico (after Lulof 2010).

Based on comparison with similar objects, there are two hypotheses:

- The lower part had the form of a simple concave rain gutter, cilindrical or more rectangular in shape, possibly with stylised fangs.

- The lower part had the form of a proper mandible.

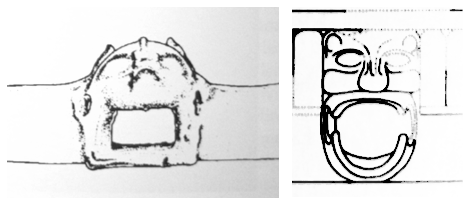

Feline head waterspouts from the Etruscan cultural zone.

Feline head waterspouts from the Etruscan cultural zone.

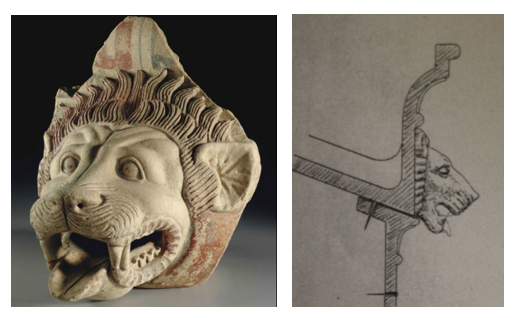

A number of 7th and 6th century BC parallels from the Etruscan cultural zone would argue for the first option. These lion head waterspouts are relatively modest and stylised moulded objects. They are however less naturalistic in their depiction of the features of the animal than the Caprifico lion head. If we look at the Greek cultural zone in the south of Italy, we note that lion head spouts are much more elaborate and naturalistic in form. They are nevertheless still quite dissimilar from our lion head, not in the least because the lion head from Caprifico seems to depict a lioness rather than a male lion with manes. Examining the head in the area of fracture, there is no indication of a transition into a different geometry as one would expect if the lower part was was a cilindrical gutter, which may support the second hypothesis. Nevertheless, the lower part may still have been severed above the point of this transition. We must therefore accept that we are not completely sure about how the lower part looked.

Male lion head waterspout from the Greek cultural zone in southern Italy.

Male lion head waterspout from the Greek cultural zone in southern Italy.

An alternative reconstruction of the lower part of one of the Caprifico lion head waterspouts (after Lulof 2010).

An alternative reconstruction of the lower part of one of the Caprifico lion head waterspouts (after Lulof 2010).

The colours

The original object has traces of the paint that was used, so we are relatively certain about the colour scheme: brownish red, dark brownish red, black and cream/white. The same colours were also found on the other architectural elements.

The revetment plaque

Many fragments of such plaques have been found at the site of the temple, although none of them with an attached lion head waterspout. We possess also fragments of this particalular type of plaque with curved cut outs in the lower corners. The cut outs received the similarly curved imbrici, architectural elements that covered the seams between the roof tiles in Roman and Greek architecture.

Roof tiles

The roof was covered with large ceramic roof tiles, known as tegulae (singular: tegula) and imbrici (singular: imbrex). The first refers to the flat tiles, the second to the curved tiles that protect the seams from rain water penetration. Such tiles were standard in Etruscan, Roman and Greek architecture and although many slight geographic and temporal variations in shape and fabric occur, the general principle remains the same and is used to this day. Wikipedia page about the imbrex and tegula.