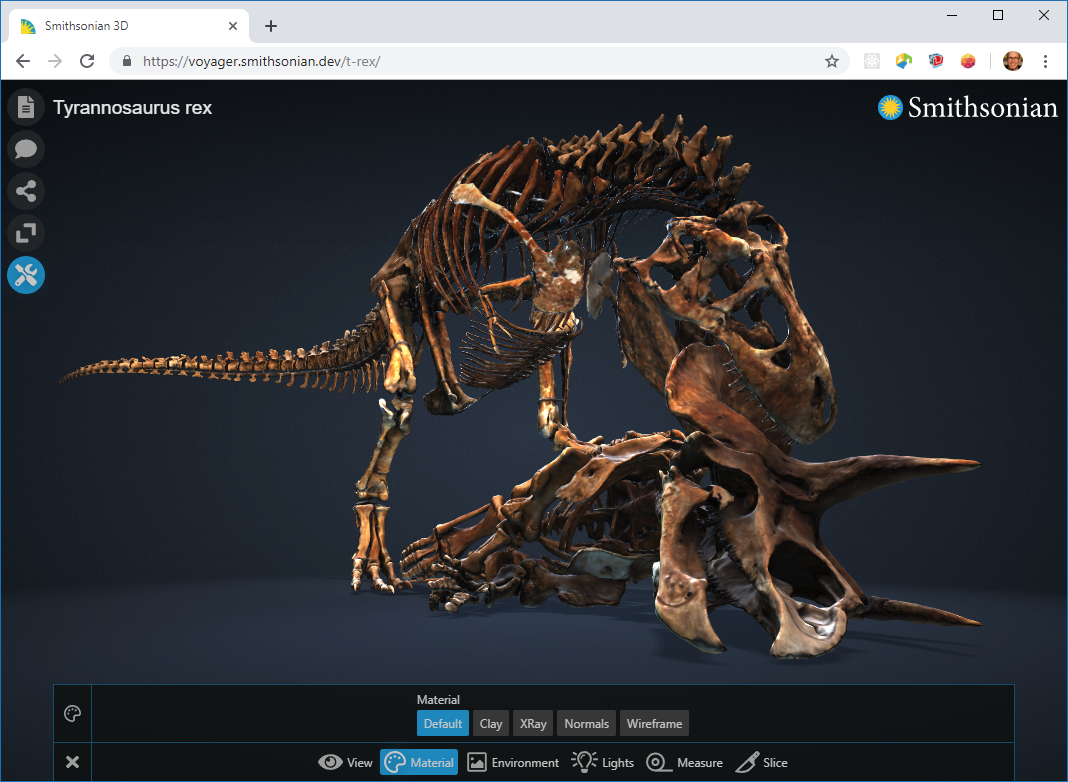

During the course Digital 3D Techniques and Methodologies for Conservation and Art Technological Research, students learn to digitally restore cultural heritage objects using 3D technologies and computer graphics software. Case studies span a wide range of applications (from ceramics and paintings to textiles and historic interiors). Recording and modelling methods include laser scanning, photogrammetry, and 3D modelling from scratch using the open-source software Blender. Since most students are new to Blender, the course includes dedicated lessons to build their skills. By the end of the course, they can perform digital restorations of damaged objects, restore colour through texture painting, and use Blender’s annotation tools to digitally document their observations. The course also emphasises digital restoration ethics and best practices to ensure restorations are clearly distinguishable from the original (digitised) artifacts.

Fig. 1 Example of one of the in-class exercises: Digital reassembly of a broken artifact in Blender

Grassroots grant for “Immersive Virtual Reality environment for digital restoration practices”

The techniques taught in this course offer a safe, reversible, and non-invasive approach to restoration. However, students often face challenges when navigating the 3D space and performing restoration tasks using a mouse. For this reason, the exploratory project “Immersive Virtual Reality environment for digital restoration practices” was initiated to evaluate whether performing some restoration procedures in a Virtual Reality (VR) environment could help mitigate some of the challenges that students encounter. This project was financed by a grassroots grant from the Teaching & Learning Centre (TLC) of the University of Amsterdam.

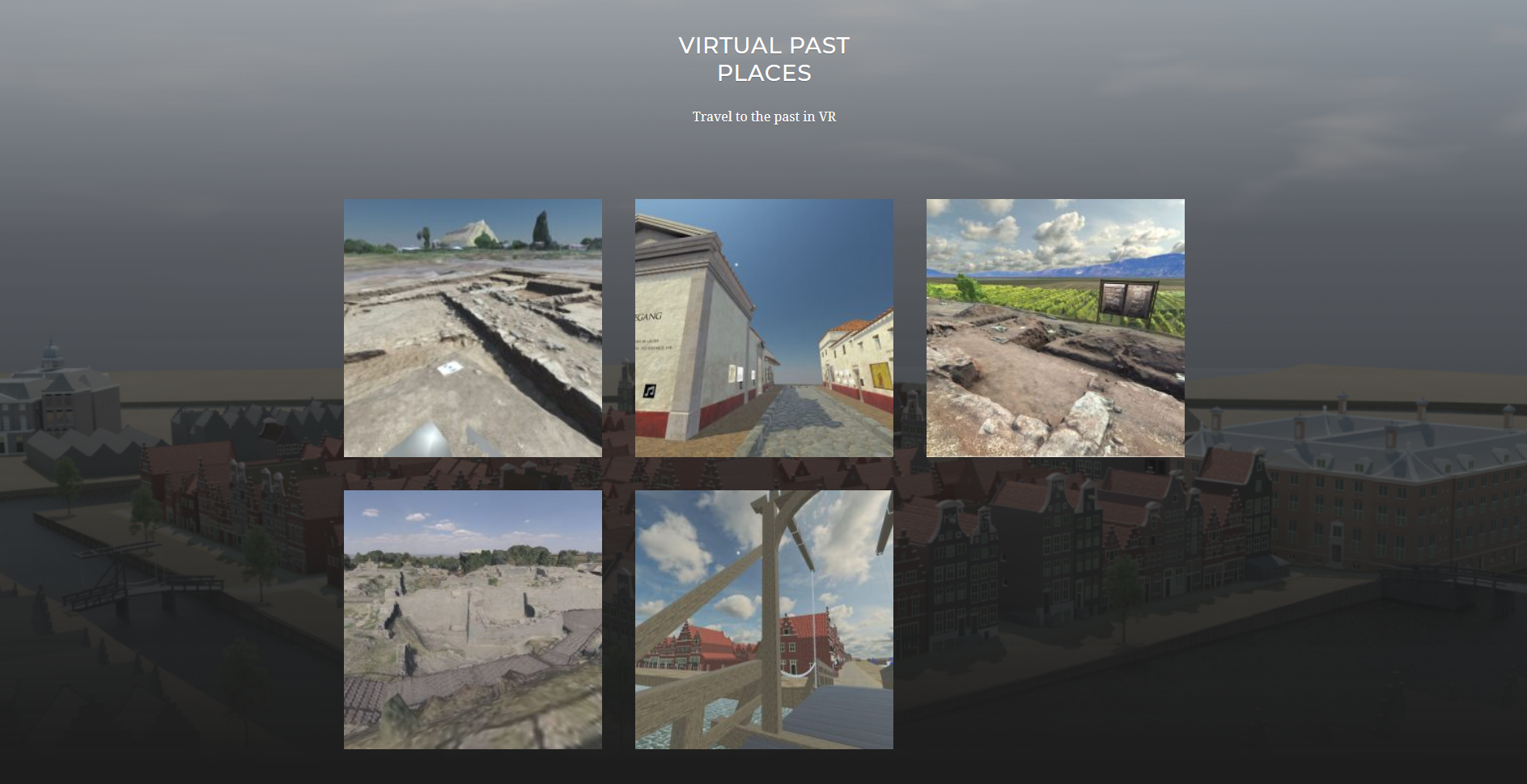

The test course ran from October to December 2024, and the VR try-out session occupied one afternoon. The number of students in this course were 14 and their feedback on the VR experience was gathered via questionnaires in Qualtrics that were adapted from the questionnaires used for the Virtual Past Places project so that the results could be eventually compared.

From a didactic perspective, this grassroots project aimed to understand the effectiveness of immersive VR in enhancing students’ learning and application of 3D restoration techniques. Specifically, it sought to determine whether VR can:

1) Improve students’ spatial understanding and navigation of 3D environments;

2) Make the restoration process more intuitive and efficient;

3) Reduce the challenges and frustrations often associated with traditional 3D methodologies;

4) Increase student engagement and interest in the subject matter.

Ultimately, the project hoped to contribute to the development of more effective, engaging, and intuitive teaching methods in the field of digital 3D restoration.

From a technical standpoint, this project aimed to:

1) Evaluate the feasibility and efficiency of integrating VR technology into the existing 3D restoration workflow;

2) Understand the technical challenges involved in creating an immersive VR environment that accurately simulates real-world restoration practices;

3) Assess the performance of the VR system in terms of speed, accuracy, and reliability in the restoration process;

4) Explore the potential for scalability and further advancements of the VR technology in the field of digital 3D restoration.

VR experiment setup

The Meta Quest 3, part of the 4D Research Lab equipment, was used as the VR headset to develop and run the try-out session. Initial efforts focused on exploring the capabilities of running a VR environment within Blender aiming to evaluate and, if needed, extend open-source tools to support a digital restoration workflow. Several existing software applications – such as Freebird VR, Gravity Sketch and PolySketch – were assessed for their suitability in this study. However, the current state of these tools revealed significant limitations: key features such as loading existing 3D models and enabling intuitive interaction with objects were either missing or insufficient, and compatibility issues further hindered seamless use. Due to financial and time constraints, developing custom software from scratch was not feasible. Ultimately, the choice fell on Adobe Medium, a free sculpting application for Meta Quest: its ability to import and intuitively manipulate 3D models, along with its comprehensive set of features, including texture painting and clay addition made it well-suited to the project’s needs.

To enable a direct comparison of experiences, three VR exercises were designed to mirror the restoration procedures previously taught in Blender. In the first exercise, students worked on the same object they previously worked on in Blender replicating the procedure of manipulating, reassembling, and restoring its broken rim and handle (see video below). The second exercise involved texture painting some of the restored pieces of the vessel, and the third focused on adding clay to fill in the chipped areas.

Fig. 2 One snapshot from the course VR try-out session (image author)

Video screencast showing one of the exercises that students had to perform in VR:

Feedback and evaluation

Student feedback highlights diverse experiences with the VR environment. Specifically, to the question How does the restoration process in VR compare to the restoration in Blender? They replied:

- “I think it was a little bit easier […]. It’s more intuitive since you can rotate and move things in relation to your body instead of in relation to a set point”

- “Very different. Feels like you have more hands-on things once you understand how VR works”

- “I liked it more as I am more of a hands-on person than computer person. With more practice I would definitely prefer it over Blender. It is just hard on the eyes”

- “The way they work is in some ways similar, both can be intuitive once you are familiar with the controls, but it takes a while to get used to for both”

- “Transformations of the objects are much easier to align in VR, but it feels as though the clay adjustments would be more difficult than additions done in Blender”

- “The process in VR is a lot faster. However, it is also a lot less precise. The VR program doesn’t allow for the same number of options and detail as Blender”

- “I did a bad job in VR because it was a bit hard to do perfectly, less control than in Blender”

Overall, questionnaire results indicate that object transformations (such as scaling, rotating, and navigating around 3D models) are more intuitive in VR, making basic interactions easier. However, tasks requiring greater precision (like adding clay for restoration) proved more challenging in the VR environment. Further research is needed to determine to what extent these difficulties stem from the inherent limitations of current VR technology or from constraints specific to the Adobe Medium software used.

Another question I asked students was: To what extent do you think VR can add value to the restoration process?

- “I think that at this point in time, the process is still in its infancy so there is a limit to the quality that you can achieve in VR, though this will change as time passes”

- “I believe that VR will take an important part in the evolution of the restoration field”

- “I think it depends on the object. For many objects I think it would just be easier to restore them physically”

- “I feel like most the things we need to achieve can already be done in Blender so in that way VR doesn’t add much but it is still fun to play around with, it makes the process feel more like a game but also it seems more physically tangible somehow”

- “It can be useful in making more dramatic visual changes which carry ethical concerns […] or testing out different reconstruction options without committing to the materials of the reconstruction”

- “I think VR can be a quick way to test restoration options or visualize the appearance of possible treatments. With more development, the programs in VR could become more powerful and useful”

- “If you’ve got the time and resolution is great. I think it’s a great tool, but right now I did not think I was that successful”

- “It was very difficult to sculpt, and I feel a traditional fill process/3d scanning/modeling on a computer is more straightforward”

Students recognised some advantages of VR in restoration practice, including a more tangible and playful interaction with the object. However, the specific tool used for the exercises will still need further development to make it useful to address all the procedures that restorers undertake. Also, the VR headset was experienced as quite heavy by some students which made the tasks less comfortable to carry out.

Conclusion

This exploratory study shows that current software and hardware limitations of this specific setup hinder the effectiveness of the VR environment for restoration practices, where accuracy, precision, and attention to detail are crucial. At the same time, it reveals the significant potential of VR to expand the toolkit available to restorers, enabling them to experiment with fragile materials in a safe, reversible, and engaging way. Furthermore, it highlights the valuable role that custom-made software development can play in advancing VR-based restoration practices.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Markus Stoffer for helping me with setting up the Adobe Medium environment in the Meta Quest and the VR try-out session; Tijm Lanjouw for his advice during the VR development, and Jitte Waagen for sharing the Virtual Past Places questionnaire.